Naomi Long Eagleson is a book editor and writer in Los Angeles. She is the author of Radiant Field, a chapbook published by Tinfish Press. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a BA in English from the University of Hawai‘i. Her poems and reviews have appeared in Arts & Letters, Words without Borders, and Mānoa: A Pacific Journal of International Writing, and in the anthology Century of the Tiger: One Hundred Years of Korean Culture in America. She is a former member of the artist group Orientity and has exhibited work at the Kyoto Art Center and the Fringe Club in Hong Kong.

Naomi Long Eagleson is a book editor and writer in Los Angeles. She is the author of Radiant Field, a chapbook published by Tinfish Press. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a BA in English from the University of Hawai‘i. Her poems and reviews have appeared in Arts & Letters, Words without Borders, and Mānoa: A Pacific Journal of International Writing, and in the anthology Century of the Tiger: One Hundred Years of Korean Culture in America. She is a former member of the artist group Orientity and has exhibited work at the Kyoto Art Center and the Fringe Club in Hong Kong.

Website ♥ Facebook

Statement

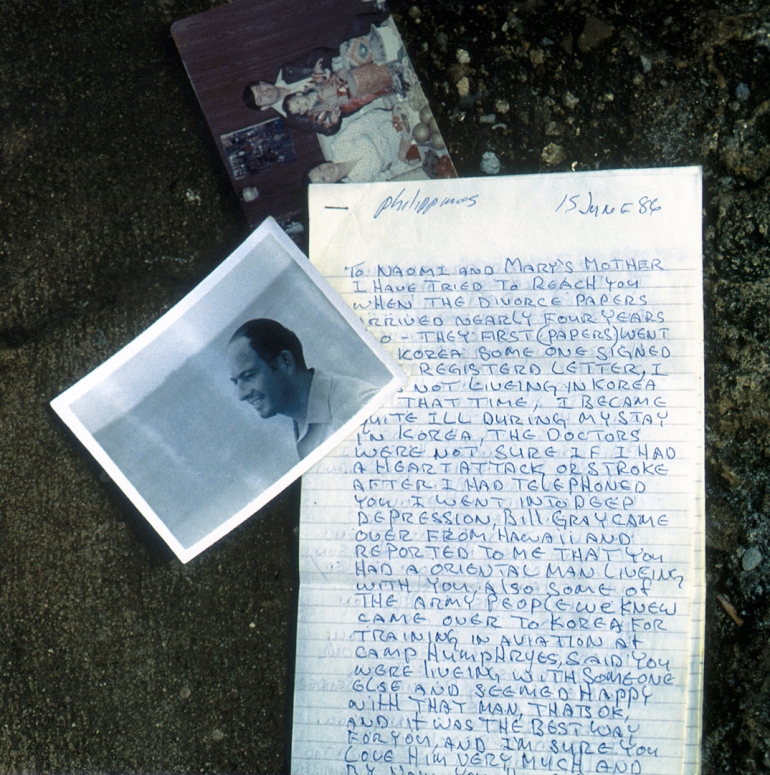

There are men in our lives who have been permanently altered by war. Fathers, brothers, and lovers. They leave for Iraq or Afghanistan as people we thought we knew, and return home as strangers. My father had been a soldier and medic in Vietnam and when he returned to the States, he brought his ghosts with him. They lived with us in our little apartment in Hawaii. They kept him up at night and drove him to drink, until he died of a heart attack thirty years later. He and his fellow vets would swap stories of the war, stories I overheard and absorbed as a child and which slowly and invisibly altered me. By the time I was fifteen, all I wanted to be was a combat photographer. I’d fantasize about walking through war zones and taking photos of the madness and horror unfolding around me. When I imagined myself in these places, I felt at home.

Thankfully, I never took that career route. But years later, while I was living in a small desert town, I met a man who had been a guerilla fighter in El Salvador. He had been living in exile in the US for ten years. He was in his mid-thirties and working as a muralist. As we traveled the desert in his green RV, he’d tell me stories about his war and his dead. Like my father, he too was haunted. Then one day, during an argument, he snapped, and it was as if the war had returned. And I had become his enemy.

Although more women are fighting in wars, the majority of soldiers are men. When they return home, when their paths cross with ours, their wars become our wars. As wives, sisters, and daughters, we feel for these damaged men; we seek to understand them, and to heal them. But sometimes the violence and paranoia, the axiom of war they practiced out in the field—to kill or be killed—erupts in our living rooms, and the only way we can protect ourselves is to leave. By writing about these men, by recreating their voices in my work, I can draw close to them while maintaining a safe and necessary distance.

I am,again, very moved by the statement of the effects of war on men –and on women. This is the voice we all need to hear.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Adele.

LikeLike

This writing reaches into me.

It is oddly familiar, yet foreign.

My mother shared war stories from Korea often. Brian, he could not help telling war stories, repeatedly. It was the only way. Thanks for sharing your writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Suzie, thanks so much for sharing your thoughts. I love what you say, that “it was the only way” for our father to cope, which was to keep retelling his war stories.

LikeLike